History of Original Beaver Baffler.

The original Beaver Baffler concept is not new, it was first described by Stan Guenther, a former trapper, game warden, wildlife biologist and beaver authority for the Washington State Department of Game. Stan Guenther described his successful Beaver Baffler in the July 1956 edition of the Washington State Game Bulletin, Volume 8 No.3.

Stan had spent many hours trapping and removing nuisance beaver, far too often from the same location, and figured there had to be a better way. He wanted to discourage the beaver from building or enlarging a dam, instead of removing them. From experience he understood beaver always built dams across a stream, but not up the stream. A simple elongated 3-foot-wide protection fence oriented upstream takes advantage of the beaver’s instinctive avoidance of building dams up stream. Stan found that beaver often tried to repair their dam for a few feet but became baffled when

forced to build upstream and never finished building all the way around an elongated fence. Thus, the original Beaver Baffler fence system concept was created.

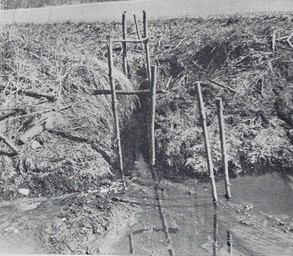

The 1956 Beaver Baffler was a low tech, low cost, but effective, structure. Original pictures are scarce but indicate the use of a 3-foot high, 12.5-gauge woven wire fence used for deer or sheep. No posts were purchased as the 1956 pictures show that stakes used to hold the beaver baffler fence wire upright were small trees and tree limbs salvaged from the dam itself and probably cut by the problem beaver.

The original Beaver Baffler was also described and recommended in at least four different USDA Forest Service publications regarding wildlife management and animal damage control in 1957, 1978, 1983, and 1994.

.

.

.

.

Washington State

Game Bulletin

July 1956 edition

Volume 8 No. 3.

A Beaver Baffler

By Stan Guenther

Washington Game Biologist

Man’s attempts to match wits with the eager beaver in his persistent building of dams in ditches and culverts has measured the patience of many farmers, road men, and game department employees throughout the nation.

A farmer may remove a beaver dam from his irrigation ditch each morning as regularly as he turns out his milk cows. A road maintenance man finds that in a year’s time he has a pile of mud and sticks as large as his truck, all of which he has laboriously removed from one culvert. In addition, there are his thoughts and language when he finds the culvert is plugged tightly halfway between the two ends.

Mr. Landowner goes down to the lower 40 to mow his meadow hay and finds that half his field is under a foot of water. After tearing a hole in the beaver dam that caused all the trouble, he lights a kerosene lantern and places it at the water’s edge. Next morning it is woven into the new dam.

Another man has it all figured out. He strings a number of tin cans on a wire just above the water. But after a few nights of observations, the beaver figures that he and his new bride are being charivaried, and gayly builds a new dam on top of this rattling outfit.

Creosote, crankcase oil, and similar smelly liquids have been poured on and around unwanted beaver haunts. Commercial animal repellants have been tried. Some of these discourage the beaver for a few days, but after the smell has been dissipated by the heat of the sun or washed away by rains, he goes right back to toting mud and sticks.

It has been found that old sacks placed in the pens of captured bear or cougar collect enough scent from these natural enemies of the beaver so that when they are hung over his dam, he steers clear of the location for a few days and sometimes weeks. But as soon as the odor begins to leave, work resumes as before.

Often a beaver becomes discouraged and moves on after all the brush and food have been removed for a considerable distance along a stream. However, this is expensive and time consuming on a wooded stream. Besides, next year the job has to be repeated.

Numerous types of culverts have been tried. In small streams logs have been laid from the culvert out into the beaver pond, so water can seep in between the logs and then out the culvert. Other inventions include extending culverts out into the beaver pond. These extensions have openings on the bottom or perforated holes the entire length to allow water to pass through.

In some cases, these contrivances puzzle a beaver several weeks before he figures out the situation, but his uncanny senses and engineering mind will find the answers, and all holes are eventually plugged.

A ”beaver proof” setup was once installed near Deer Park, in eastern Washington. A low beaver dam in the creek originally did no harm, but it was gradually raised until it flooded a large meadow. It was estimated that if the water level could be lowered one foot, the meadow would again become dry and the landowner happy.

A large culvert was placed half way down in the dam and extended 12 feet out into the beaver pond. The free end of the culvert was held up by poles and covered with a heavy screen. This installation was theoretically a sound

one as the pond had been dug out until the end of the culvert was 10 feet above the bottom.

Summer went by and the farmer’s meadow remained dry, but as winter approached, the field again was inundated. An investigation showed that the weary beaver had finally completed the almost Herculean task of building up the bottom until it entirely buried the culvert, even though several tons of mud had to be used to complete this operation.

Imagine a small marshy lake which produces good trout fishing. At least it does until a beaver dams up the outlet in the fall and raises the water level a couple of feet. When this freezes over during winter, decomposition of the newly flooded vegetation under the ice uses up all the oxygen, and by spring the lake is no longer productive. The fish have all succumbed to lack of oxygen.

The usual cure for beaver damage is to remove the beaver. In the winter they are turned into fur coats. In the summer the beaver are live-trapped and move to new locations. However, too often live-trapping beaver from damage areas is only temporary relief as other beaver will soon move in if the location is suitable. Live-trapping beaver from some areas seems to be an endless job. It is also often expensive to the Department of Game. Sometimes five or six trips are needed to successfully live-trap a pair of beaver, and longer to remove an entire colony.

A fence built in front of a culvert doesn’t discourage the beaver from placing his dam against the fence, but such a dam is much easier to remove than trying to unplug a culvert. Various types of fences have been tried, some of which were successful for a year or more.

.

.

.

.

Recent experiments have shown that one type of fence can be wholly successful. These fences have been in operation for three years and have stopped the beaver in the most aggravated cases.

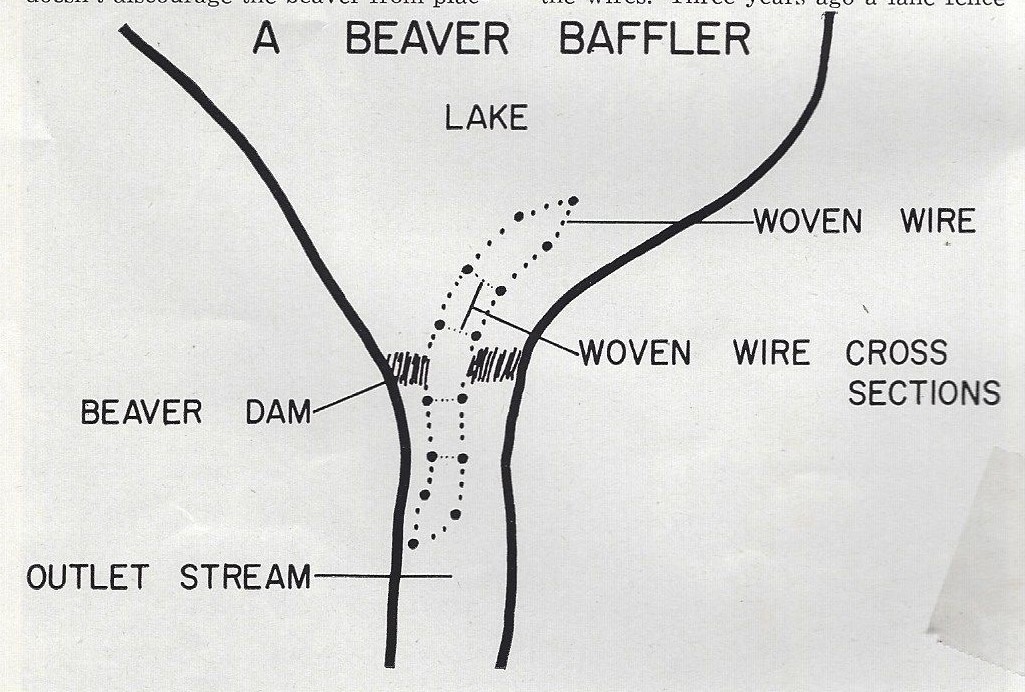

This “beaver baffler” consists of a narrow lane of woven wire. This lane should be at least 2 ½ to 3 feet wide. It is run up the stream bed for 30 or 40 feet from the culvert. In cases where a beaver dam is being constantly rebuilt and floods a field or dams the outlet of a lake, a fenced lane is started 15 to 20 feet below the dam and extends through the dam out into the lake 30 to 40 feet. This extension is built in one to three feet of water and may follow along close to shore if the lake or pond is deep. If the fence is properly installed the beaver would have to build a dam up one side of the lane and down the other. They have never been known to try this. Instead, they concentrate their efforts in trying to push mud through the fence, crawl over, or dig under the wire at the culvert or dam site. Posts must be placed close enough together to hold the wire at the bottom of the pond.

Earlier experiments with lanes 1 ½ feet wide were not always successful as the beaver were able to push the wire together with mud and sticks.

A persistent beaver can dig under the fence, but his work is halted when the fenced-in lane has several cross sections of woven wire primarily near the place he has been accustomed to working. This prevents the beaver from carrying material inside the lane. Sixteen such installations are successfully installed in Northeastern Washington.

Several of these fences had to be remodeled before they were successful. On one a beaver chewed off a corner post which allowed the two sides to come together, and a dam was immediately built by working on both sides of the wires. Three years ago, a lane fence built out from a culvert discouraged the beaver for

six months. Then they built a dam 15 feet below the road and again everything was flooded. A lane was extended from the road down through the new dam and 20 feet beyond. No more beaver work has been observed here.

Fences are normally built about three feet high. If it is necessary to run the lane in three or more feet of water, high wire must be used. The cost of new material to install a 30-foot lane fence is usually less than the cost of making four or five trips in an attempt to trap the beaver.

Streams that are subject to high floods have not been successfully fenced. But in general, these “beaver bafflers” have saved many people considerable labor, expense, and temper, wherever they have been used.